Where I live, we’re fortunate to have a good, publicly available music library within easy reach. Most of the amateur orchestras in the area make it their first stop when finding sets of parts to play from.

Normally the music arrives with bowings, fingerings and other markings inherited from previous users. Often this helps: it saves you from having to work everything out from scratch, and sometimes someone will have come up with just the right solution to make something work. I don’t normally rub the markings out until I’ve established whether they’re any good.

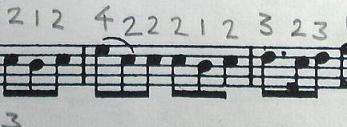

Sometimes, though, you wish the previous user had left their pencil at home:

And that’s what the music looked like after I’d started erasing the fingering.

You can learn a bit about the player by seeing what they’ve written in. This one had probably had a teacher who at some time stressed the importance of knowing what finger you’re going to use for every note in a piece, and of writing it in the music. And you certainly know precisely what finger they’re using for each note in the passage. Every single note. This is a player who follows their teacher’s instructions. Also a player, I think, who finds second position demanding but is nevertheless determined to use it where appropriate.

And in fact it’s good fingering: it works well, and is pretty much what I ended up using in the concert.

But actually, a part which has fingering written in like that is a nightmare to use. More on that in a moment.

Let me explain a little about basic violin fingering. In general (there are exceptions), it’s based on the concept of positions. These simply refer to how far up the neck of the violin the left hand is. For example, in first position your hand is next to the scroll, and your first finger plays the next note up from the open string. As you move up the scale, each next note up simply uses the next finger. For a semitone the fingers are close together; for a tone they’re further apart. When you run out of fingers, you move to the next string.) In second position, your hand is one note further up the violin. And so on.

So, as far as basic fingering goes, once your hand is in a given position, the fingers to be used are already known. Same note, same finger. And there’s definitely no need to do this:

“4 2 2 2 1 2″—once you’ve put your 4th finger down on the E, what other fingers could you possibly be using for those notes? And if you’ve got three identical notes in a row, is there really any doubt what finger you’d use for the second and third ones? The finger doesn’t even move—it just stays on the string for those three notes while the bow plays them. As far as the left hand is concerned, it’s just one note.

I think I understand what the player was doing. Many violinists have a great fear of playing in second position. I think that’s partly because it’s traditional to learn first and third positions before moving on to second. This makes second position quite a shock, because you’ve become used to the idea that odd-numbered fingers play on the lines and even-numbered fingers play in the spaces. With second position it’s the other way round, so it feels quite wrong and very confusing. And this particular player probably found it confusing for every note, so wrote the finger in for each one. Which I suppose is just about OK for purposes of slow practice. But for some reason they continued writing them all in, even when they were back in much friendlier first position.

Does this overkill matter? Well yes, actually.

When you read a piece of music, you’re taking in information. The more information there is, the harder that is to do. A finger for every note is simply too much to absorb, especially at speed. The redundant fingering gets in the way of reading the music. The stuff you don’t need to know (or rather, automatically know) conceals the stuff that’s important.

Occasional fingerings in the passage have been circled. Those are the position changes; the player presumably circled them to notice them and remember to do them. And the circling proves my point, really. They’re the ones that actually matter, and they were getting lost in the sea of redundant ones. For me, even the circling doesn’t help much: to read the fingering comfortably I need to get rid all the others. That lets me see where the position changes are and be ready for them. I can see that they’re coming up well before they arrive.

The other basic problem with filling the music with fingerings like that is that there’s no room to write anything else in. Bowings, for example. In this extract, there are several places where it’s crucial to know what bowing to use: the “4 2 2 2 1 2” bar is one such place. The slur in that bar means you’ve got to do something to avoid having “upside down” bowing in the next bar, and you need to mark just what it is that you’ll do.

What you should write in a part are the essentials: where to change position, what dynamic the conductor has asked for, little tricks of fingering that depart from what would happen automatically, whether a particular note is to be played as an open string or with the fourth finger, and so on. Bowings that depart from the instinctive ones. The less clutter there is in the part, the clearer your picture will be of what to do when playing. But also, the kinder you will be being to the next person to play from the part. They’ll be able to see what you did, rub it out if they don’t want it, and write their own essential markings during rehearsal without the stress of frantically erasing yours in the few seconds they have before playing resumes.