You’ve probably noticed two trends in the instruction manuals or leaflets which come with consumer items. For one groups of items—mobile phones for example—the trend is towards giving less and less useful information. For example, my new phone has a red light on the side which sometimes flashes. It must do this for a reason, to indicate something, but I’ve no idea what and the manual doesn’t tell me. In fact much of the manual consists of sentences beginning “You can . . .” which mention a particular task but don’t actually mention how to do it.

The other trend is towards giving more and more unnecessary information—for example, telling you that candles burn and that the flame is hot.

Many sets of instructions are also written in barely intelligible English, translated from another language by a non-native speaker of English. Personally I think such translations should be required to meet a minimum legal standard, since confusion can in some cases be dangerous and in others can make certain features of a product unusable. If the instructions for a feature can’t be deciphered, then the feature is effectively not there and you may just as well have been sold a faulty product.

A couple of weeks ago I bought myself a Russell Hobbs coffee grinder, in order to let me drink nice, freshly ground coffee. It works very well.

My first reaction to the instructions that came with it was that it was a breath of fresh air to read ones which were obviously written by someone who knew English. Every word was intelligible.

My second thought was that they were rather detailed, but since a lot of the detail concerned safety and the reasons for various things, that was still OK.

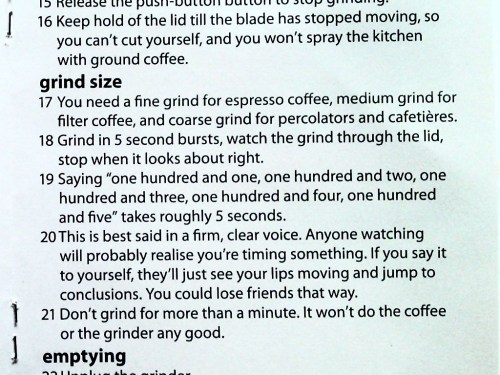

What I wasn’t expecting, though, was the advice on personal relationships in step 20:

Item 16 is reasonable, though amusingly worded. So are items 17 and 18, though the writer appears either not to have heard of semicolons or to have missed an and out. Item 19 is certainly an adequate way of counting approximate seconds. But item 20???

That made me laugh out loud, but I’m wondering how on earth it made its way into an actual instruction booklet. In a draft as a joke when someone had been drinking, maybe . . . but the final booklet? For a well-known manufacturer? Do they know what is going out in their name?

I confess that when I grind the coffee, I don’t count in a “firm, clear voice”. I either time the bursts with my watch, or count quietly and take the risk of people jumping to conclusions.